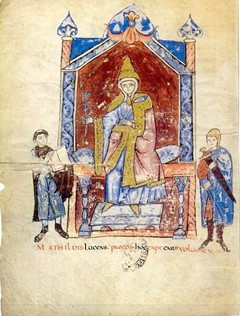

Matilda of Canossa.

The life and vicissitudes of The Grand Countess – Part 1

Matilda, bright torch blazing within a pious heart. She raised the numbers of weapons, resolutions and vassals. She saw to dispensing her own magnificent treasure, instigated and conducted battles. Should I cite one by one the works carried out by this noble lady, my verses would proliferate to the point that they became as countless as the stars...

- Donizone – Vita Mathildis

No medieval source has left us with direct information on the birth and childhood of Matilda of Canossa, however it is possible to convincingly reconstruct the story of those years on the strength of what happened to her family.

Matilda was the third-born daughter of Boniface, the count of Canossa, known as “The Tyrant”, sole heir of the grand dynasty of the Canossa, Lords of Tuscia, and Beatrice of Bar (later of Lorraine), from a noble imperial family related to the emperors Henry III and Henry IV, of whom she was respectively niece and first cousin, as well as Pope Stephen IX.

Historians agree in establishing Matilda’s date of birth in the year 1046, since the Countess’s biographer, the monk Donizone, states that in the year of her death, 1115, she was sixty-nine years old. As regards her place of birth, even though various opinions exist, it was very likely to be Mantua, since the Court of Canossa was residing there that year.

Little is known of Matilda’s earliest childhood apart from the fact that she led a peaceful life devoted to study. In fact the little girl grew up learning to read and write and could speak fluent German and French. Her happy childhood was disrupted by the tragic death of her father, Boniface, who was accidentally killed by one of his own vassals while out hunting.

After the death of her husband, Beatrice of Lorraine found herself in great difficulties administrating such a vast fiefdom, and turned to her uncle, Pope Leo IX, for help. In exchange for this help, he repossessed the assets that Boniface had confiscated from the churches, and also secured other benefits for rectories and monasteries.

But another tragic event was waiting to mark Matilda’s early years; the year after her father’s death also her brother, Federico, the legitimate heir, and her sister, Beatrice, died, most likely because of accidental poisoning.

At this point, her mother Beatrice confessed to the Pope her longing to retire to a convent together with Matilda who was still a young child. But the political and economic interests involved were too important to allow the heirs of that huge fiefdom of the Canossa family to give it all up.

And so Leo sent one of his emissaries to Canossa, a certain Hildebrand of Sovana, the future Pope Gregory VII, who changed Beatrice’s mind about the convent idea and suggested a “political” marriage with Godfrey III, called the Bearded, a powerful and authoritarian German duke, who was a relative of hers.

Beatrice chose to accept this union, blessed by Pope Leo, together with a promise of marriage between Matilda and Godfrey IV (nicknamed “The Hunchback”), the natural son of Godfrey III.

The wedding of Matilda and Godfrey IV took place in Germany in 1069. The groom was a fearless, upright youth afflicted by certain physical defects, but despite this, conscious of the noble duties she had been educated for and after being persuaded by her mother, Matilda remained in Lorraine living with her husband. Sometime between the end of 1070 and the beginning of 1071 the young bride gave birth to a baby girl she named Beatrice. However, it was a difficult birth and after only a few days, the little girl passed away: it was the 29th of January 1071. On the 29th of August of the same year, Beatrice of Lorraine had the monastery of Frassinoro built in the Apennines near Modena, as was the custom amongst the aristocracy, so that, ‘the soul of my late granddaughter, Beatrice, might receive grace.’

But Matilda was not welcome at the Court of Godfrey, and the following year, feeling threatened, she fled to her mother at Canossa. Godfrey attempted to rejoin Matilda, more out of a question of politics rather than love, but it was impossible to reconcile his intimate alliance with the emperor Henry IV with the staunch relationships that bound Matilda to the Pope and the interests of the pontifical state.

Then all of a sudden, in 1076, Godfrey IV met an atrocious and violent death, probably at the hands of a hired assassin. At this point, Matilda and Beatrice retook possession of all their property and jurisdiction across the Italian peninsula, thanks to which they were now able to count definitively on the support of Hildebrand, the new pontiff, known as Gregory VII.

Geographically speaking, the estates of the Canossa stretched across a large part of central and northern Italy, from Tuscany which Matilda was marchioness of (the most important authority in Italy after the sovereign), as far as the territories of Reggio Emilia, Parma, Modena, Ferrara, and Brescia along with Cremona, Verona and Mantua.

To understand the historical and political context Matilda was moving within, at the point when she would be invested with all the responsibilities linked to her boundless, powerful fiefdom, we must turn our attention to the two great rival personalities who would dictate the events of the 11th Century: Pope Gregory VII and the Emperor Henry IV.

Gregory was a resolute man, committed to giving a new lease of life to the Church; he dreamed of freeing the sepulchre of Christ from the infidels, getting rid of the intrusive power of the Normans, and of reunifying the Eastern Church.

But, above all else, he wanted to bring the investiture of bishops back under the control of the Church of Rome, something which, at that time, was decided by the Emperor.

For a while the Emperor Henry IV, who had numerous problems in Germany, tried the avenue of conciliation and compromise but, after the Pope adamantly stressed his right to nominate bishops at the 1075 council, a dispute became inevitable.

And thus one of the cornerstones of imperial power would vanish. In fact, at that time, the bishops exercised authority of a feudal type, civil as well as religious. This power was fundamental to maintain imperial authority intact and a considerable economic source, since the office of bishop was frequently bought with hard cash.

Gregory was aiming at a profound reform to put an end to the outrageous spectacle of the simoniac bishops, corrupt, and often living in sin. If he could, he would have avoided clashing with the Emperor. In fact, at the beginning, he did try to explain his intentions, he did try to reach an agreement, but as a careful man who was no stranger to the ramifications of power, he kept his most dreaded arm up his sleeve: Excommunication.