Tracking Down Matilda in Italian and European Museums

Very few women have enjoyed such an important leading role in Italian and European history as Matilda of Canossa, even if in the Middle Ages she was considered of low social standing. For a good forty years Matilda reigned over a dominion which stretched over most of northern and central Italy, including Tuscany, and she was also a key figure in the struggle between the Empire and the Church.

Above all else the Grand Countess was a European women, in the current concept of the term - courageous, educated, from international stock and culture, who was a leading player on the political scene of her times profoundly influencing the social and cultural plane.

A personality who gave birth to her own legend thanks to a personal, clear-cut desire to leave her and her ancestors’ marks behind on both her land of origin and European culture.

The spiritual and religious ferment aroused by the Gregorian Reform spread throughout Western Europe. This ferment was felt particularly strongly in the lands ruled by Matilda who set up not only a powerful defensive network of fortresses and castles, but also a vast complex of places of worship, developing an architectural empire of uniform and unitary characteristics, above all in the River Po valley area, heavily influenced by the powerful Benedictine Cluny monastery. Indeed, during the XI century, Cluny foundations, linked directly to the Holy See, were to mushroom all over Western Europe and their spread also brought with it the technologies used by the monks in the construction and sculpting of their cathedrals and abbeys. Hence the Romanesque Cathedral of Modena and the Abbey of Nonantola.

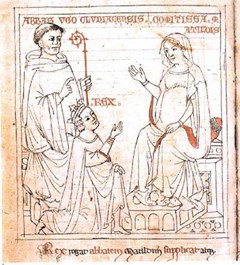

In the disturbing events which took place at Canossa in 1077, one key player was the Abbot Hugh of Cluny who took part as mediator for his godson Henry IV.

After these events Matilda bequeathed Hugh her family monastery at Polirone near Mantua.

Thus Matilda’s heritage is to be detected in the sweeping medieval architectural expression across the Po valley plain, but of her personal effects only a few objects remain: seals, sealed documents, material souvenirs which record her adventurous life and are kept in museums, libraries and archives across Italy and Europe.

From 2008 to 2009 the Province of Reggio Emilia dedicated a very special exhibition to Matilda of Canossa and her times, featuring 215 works that depicted the most salient historical events of the Countess’s life, amongst the best known in medieval history.

Amongst the works and objects connected to the Grand Countess that have reached us we must mention the De Principibus Canusinis from 1115, which is a biography of Matilda by the monk Donizone, which after various adventures over the centuries, arrived in the hands of Pope Paul V at the beginning of the 1600s, who entrusted it to the Vatican Libraries where it is still kept.

A copy of the Gospels said to have belonged to Matilda is on display at the Nonantola Benedictine Museum and the Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art. It is bound in wooden boards covered in embossed and delicately gilded sheets of silver. The same museum houses a XII century ivory casket used as a shrine.

The historical archives at Mantua and Lucca both keep documents concerning bequests of chattels and possessions to various churches.

We should also recall Henry IV in that same period. At Speyer Cathedral in Germany, on opening the tombs of the Salian sovereigns in 1900, in the tomb of Henry IV, a funerary cross, a crown, a ring, and a small reliquary-cross in silver leaf were found.

Many objects belonging to the Salian Emperors are kept at the Historisches Museum der Pfalz in Speyer.

Meanwhile, Munich’s Staatsbibliothek keeps the letter in which Henry IV tells Gregory VII he has been deposed.

Matilda’s legend has also grown thanks to the iconography recycled over the centuries after her death. Bernini produced the tomb to hold the body of the Grand Countess at Saint Peter’s in Rome; a sketch of this tomb is kept at the Musée des Beaux Arts in Brussels, while Berlin’s Kunstgewerbemuseum has on display one of eleven small bronzes portraying Matilda, again by Bernini.

At Verona’s Castelvecchio Museum we can see a splendid portrait of Matilda painted by Paolo Farinati in 1587, in which she is depicted as a knight on horseback in profile in line with the prevailing Imperial iconography, which looked back to ancient numismatics.

At Mantua the Diocese Museum is home to another superb portrait from the XVI century, while at the Palazzo della Ragione, built by Boniface of Canossa, an image of Matilda has been identified in a portion of fresco. The Grand Countess is portrayed full length, almost at natural height, and dressed in a red cloak and an Augustinian habit.

This is unquestionably the oldest image of Matilda after the miniatures illustrating Donizone’s biography.